Introduction¶

Simulation taxonomy¶

In this section, we introduce the scope and boundaries of DSOL. In order to do this, we introduce a theoretical view on modeling and simulation. According to Shannon (Shannon, 1975) simulation is the process of designing a model of a real system and conducting experiments with the model for specific purpose of experimentation. The model is expressed in a language. According to Sol, this language merely reflects a chosen vehicle of communication (Sol, 1982). Computer simulation is therefore an application domain of programming languages. Based on this, Ören et. al. (Ören & Zeigler, 1979), and Sol (Sol, 1982) introduced the following concepts:

- A model, or model system is a selected set of objects and relations describing a system under investigation.

- An experiment, or experimental frame, defines the conditions under which an experiment must take place. The experiment contains the treatments (or scenarios) to be executed.

- A simulator is a computational device for generating behavior of the model, based on the parameters of the experiment.

Based on the method of execution, Nance introduced the following taxonomy of simulation (Nance, 1993):

- Discrete event simulation in which the model specifies discrete time changes as a function of time. Time changes may either be continuous or discrete.

- Continuous simulation in which the model specifies continuous time changes as a function of time. Time changes may again be either continuous or discrete.

- Monte-Carlo simulation which uses models of uncertainty where representation of time is unnecessary. It is a method by which an inherently non-probabilistic problem is solved by a stochastic process.

Based on this taxonomy, several related forms of simulation are defined. Law & Kelton (Law & Kelton, 2014) introduce combined simulation as a form in which a model contains both discrete and continuous components. Shantikumar (Shanthikumar & Sargent, 1984) introduced hybrid simulation as a form in which a model contains discrete event and analytical components. The Department of Defense standards (Department of Defense, 1995) speak of virtual, live and constructed simulation whenever real-time, human or hardware components are involved in the specification of a model.

This taxonomy results in the first insight in the boundaries of DSOL. DSOL aims to support all of the above but Monte-Carlo. DSOL inherently aims to provide decision support for time-dependent ill-structured problems.

Requirements for a simulation language¶

In order to proof the validity of DSOL, we must understand its requirements. As will be pointed out, its requirements form an extension to the requirements given by Nance (Nance, 1993) and Sol (Sol, 1982) for any simulation language:

- to provide pseudo random numbers. A good overview of pseudo random numbers can be found in (L’Ecuyer, 1997);

- to provide a set of statistical distributions. More information on these distributions can be found in (Law & Kelton, 2014);

- to provide time-flow mechanisms to represent an explicit representation of time. More information on time-flow mechanisms can be found at (Balci, 1988);

- to provide an experimental frame so as to represent the experiment;

- to provide statistical output analysis. More information on the statistical output of simulation can be found in (Banks, 1998; Law & Kelton, 2014).

In simulation a clear distinction is made between real time and simulation time. The concept real time is used to refer to the wall-clock time. It represents the execution time of the experiment. The simulation time is an attribute of the simulator and is initialized at t=0.00. Simulation time can be stopped, incremented and take both continuous and discrete steps (Balci, 1988). Nance (Nance, 1981) formalized the time-state relations as follows:

- An instant is a value of simulation time at which the value of at least one attribute of an object can be altered.

- The state of an object is the enumeration of all attribute values of an object at a particular instant.

- An interval is the duration between successive instants and a span is the contiguous succession of one or more intervals.

- An activity is the state change of an object over an interval.

- An event is a change in object state, occurring at an instant, that initiates an activity precluded prior to that instant.

- A process is the succession of state changes of an object over a span.

Modeling perspectives¶

In order to construct a model a Weltanschauung must implicitly be established to permit the construction of a simulation language (Lackner, 1962). This Weltanschauung expresses the metamodel of the language and is also referred to as formalism, modeling construct or world-view (Balci, 1988). Literature has identified three basic world-views for discrete event simulation (Fishman, 1973; Overstreet & Nance, 1986):

- Event scheduling which provides a locality of time: each event in a model specification describes related actions that may all occur in a single instant.

- Activity scanning which provides a locality of state: each activity in a model specification describes all actions that must occur due to the model assuming particular state.

- Process interaction provides a locality of object: each process in a model specification describes the entire action sequence of a particular object.

DSOL primarily supports the event scheduling formalism (Jacobs, Lang, & Verbraeck, 2002). Process interaction has quite some multi-threaded implications when implemented in a naive way. See e.g., (Lang, Jacobs, & Verbraeck, 2003) on the dangers of specifying a process interaction formalism in Java. Absent continuations in Java, process interaction has been implemented using a bytecode interpreter, actually a Java Virtual Machine, implemented in Java (Jacobs & Verbraeck, 2004). When lightweight threads would become available in Java, a more efficient implementation of process interaction would be possible. Activity scanning is partially supported in the DEVS implementation, in the sense that the next state that is calculated with the internal transition method in DEVS is based on the state of the atomic model (Zeigler et al., 2000). An implementation that can take the full state would be extremely inefficient to execute.

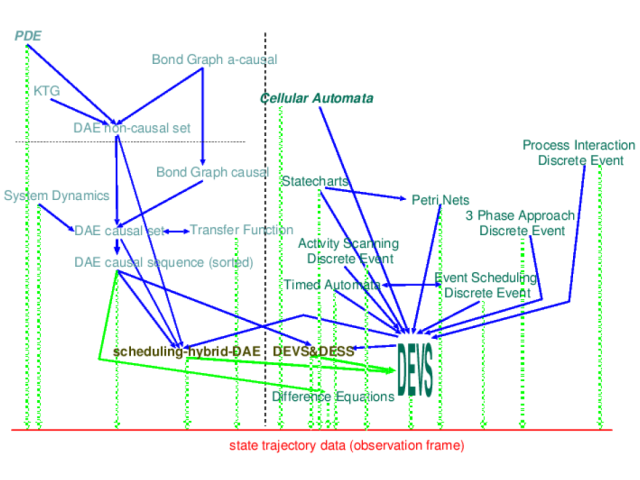

Vangheluwe and Lara (Vangheluwe & de Lara, 2002) published in 2002 a formalism transformation graph (see Figure below). The arrows in this graph denote a behavior-preserving homomorphic relationship using transformations between formalisms. Further development will show to what extent DSOL can implement these relationships and provide the full set of modeling formalisms. In different projects, a large number of formalisms have already been executed by DSOL. Several of these will be shown in the following chapters.

Besides the event scheduling formalism for discrete event scheduling, DSOL supports continuous differential equations (DESS), the atomic DEVS formalism, the parallel DEVS formalism, the Port-based DEVS formalism, the hierarchical DEVS formalism, the Dynamic Structure DEVS (DSDEVS) formalism, and the DEV&DESS formalism. Prototype implementations of QDEVS (Quantized DEVS) and Phi-DEVS (Phase-based DEVS) have been made (Seck & Honig, 2012), as well as Agent-based DEVS implementations (Zhang, Verbraeck, Meng, & Qiu, 2015) and BPMN (Business Process Model Notation) model execution (Çetinkaya, 2013; Cetinkaya, Verbraeck, & Seck, 2013).

References¶

- Balci, O. (1988). The implementation of four conceptual frameworks for simulation modeling in high-level languages. In Proceedings of the 20th conference on winter simulation (pp. 287–295). New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Çetinkaya, D. (2013). Model driven development of simulation models: Defining and transforming conceptual models into simulation models by using metamodels and model transformations. PhD thesis, Delft University of Technology.

- Cetinkaya, D., Verbraeck, A., & Seck, M. D. (2013). Chapter 22: BPMN to DEVS: An application of the MDD4MS framework in Discrete Event Simulation. In S. Mittal & J. L. Risco Martin (Eds.), Netcentric System of Systems Engineering with DEVS Unified Process. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Available from https://www.crcpress.com/product/isbn/9781439827062.

- Department of Defense. (1995). Modeling and Simulation Master Plan. https://www.dmso.mil. (DoD 5000.59-P).

- Fishman, G. S. (1973). Concepts and methods in discrete event digital simulation. New York, USA: John Wiley and Sons.

- L’Ecuyer, P. (1997). Uniform random number generators: a review. In Proceedings of the 29th conference on winter simulation (pp. 127–134). New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Jacobs, P. H. M., Lang, N. A., & Verbraeck, A. (2002). A distributed Java based discrete event simulation architecture. In Proceedings of the 2002 winter simulation conference. New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Jacobs, P. H. M., & Verbraeck, A. (2004). Single-threaded specification of processinteraction formalism in Java. In Proceedings of the 36th conference on winter simulation (pp. 1548–1555). New York, NY: ACM/IEEE. Available from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1161734.1162019.

- Lackner, M. R. (1962). Toward a general simulation capability. In AIEE-IRE ’62 (Spring) proceedings of the 1962 Spring Joint Computer Conference (pp. 1–14). New York, NY: ACM.

- Lang, N. A., Jacobs, P. H. M., & Verbraeck, A. (2003). Distributed, open simulation model development with DSOL services. In 15th European Simulation Symposium and exhibition. Erlangen, Germany: SCS Europe BVBA.

- Law, A. M., & Kelton, W. D. (2014). Simulation modeling and analysis (5th ed.). New York, NY: Mc Graw-Hill.

- Nance, R. E. (1981). The time and state relationships in simulation modeling. Communications of the ACM, 24(4), 173–179.

- Nance, R. E. (1993). A history of discrete event simulation programming languages. In The second ACM SigPlan conference on history of programming languages (pp. 149–175). New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Ören, T. I., & Zeigler, B. P. (1979). Concepts for advanced simulation methodologies. Simulation, 32(3), 69–82.

- Overstreet, C. M., & Nance, R. E. (1986). World view based discrete event model simplification. In M. S. Elzas, T. I. Ören, & B. P. Zeigler (Eds.), Simulation methodology in the artificial intelligence era (pp. 165–179). Amsterdam, Netherlands: North-Holland Publishing Co.

- Seck, M. D., & Honig, H. J. (2012). Multi-perspective modelling of complex phenomena. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 18(1), 128-144. Available from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10588-012-9119-9

- Shannon, R. E. (1975). Systems simulation: the art and science. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Shanthikumar, J. G., & Sargent, R. G. (1984). A unifying view of hybrid simulation/ analytic models and modeling. Operations Research, 31, 1030–1052.

- Sol, H. G. (1982). Simulation in information systems development. PhD thesis, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands.

- Vangheluwe, H., & Lara, J. de. (2002). Meta-models are models too. In Proceedings of the 2002 Winter Simulation Conference. New York, NY: ACM/IEEE.

- Zeigler, B. P., Praehofer, H., & Kim, T. G. (2000). Theory of modeling and simulation (2nd edition). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Zhang, M., Verbraeck, A., Meng, R., & Qiu, X. (2015). Agent-based modeling of large-scale complex social interactions. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SigSIM conference on principles of advanced discrete simulation (pp. 197–198). New York, NY, USA: ACM. Available from http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2769458.2773790.